Elon Musk’s year of controversy continues as startup Operation Bluebird attempts to take flight with its rival social media platform — “twitter.new” — by asking the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) to find that Musk’s X Corp. has abandoned its “Twitter” and “tweet” trademarks. X Corp. responded to this petition on December 16 by asking the District Court of Delaware to find that Operation Bluebird is actively infringing on X Corp.’s trademarks by publicly positioning itself to take over the world-famous branding. While Musk publicly remarked in 2023 that X would “bid adieu to the Twitter brand and, gradually, all the birds,” the USPTO and the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware will soon be tasked with determining whether the marks are deemed “abandoned.”

Key Elements of Trademark Abandonment: Non-Use and Intent Not to Resume Use

The Lanham Act provides that a mark is deemed abandoned “[w]hen its use has been discontinued with intent not to resume use.” In practical terms, a party claiming abandonment must establish two elements: (1) the mark’s non-use and (2) intent not to resume use.

Courts may infer intent to use from the circumstances. Importantly, any “use” must constitute a bona fide use in commerce — that is, use made to identify the source of goods or services and not merely to reserve rights in the mark. The Lanham Act further provides that three consecutive years of non-use creates a rebuttable presumption of abandonment, shifting the burden to the trademark owner to produce evidence of continued use or intent to resume use.

Beyond statutory abandonment, trademarks may also be abandoned in other ways. For example, owners risk losing marks when they become a generic identifier of goods or services, when the associated goods or services are discontinued, or when the owner neglects to police or protect its rights.

An Owner’s Rebuttal: Proving Use or Intent to Resume Use

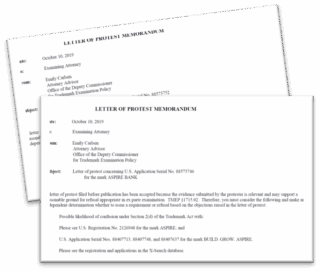

A trademark owner’s strongest chance of surviving an abandonment claim is evidence of the mark’s current use in commerce, which may include advertising or marketing materials, website screenshots, product packaging or labels, social media promotion tied to sales, or shipping and transaction records. Even where a mark has fallen out of active commercial use, an owner may rebut abandonment by demonstrating a documented and objective intent to resume use. Such evidence can include business plans referencing the mark, product development timelines, licensing negotiations, draft marketing materials, or internal communications discussing relaunch plans.

What Happens After Abandonment?

Once a trademark is deemed abandoned, for all practical purposes, the owner loses all rights associated with the mark. Any protection tied to prior use is extinguished, and the mark generally returns to the public domain — available for adoption and registration by others. While a former owner may attempt to revive the mark, prior registrations typically provide little advantage. Abandonment is, in most cases, permanent.

Potential Abandonment of the Iconic Blue Bird

Despite X Corp.’s successful renewal of its “Twitter” trademark in 2023, Musk and the X Corp. formally dropped the Twitter branding in July of that same year. Operation Bluebird is thus poised to argue that, as of July 2026, X Corp. has presumptively abandoned the mark due to three years of non-use.

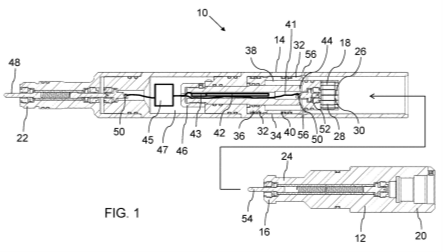

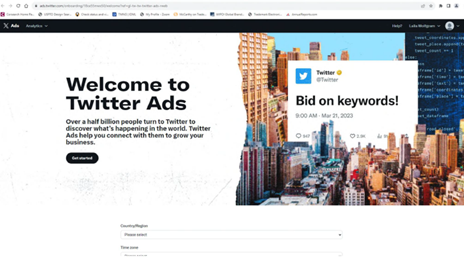

Notably, X Corp.’s renewal filing included a screenshot of a “Twitter Ads” webpage featuring both the “Twitter” word mark and the iconic blue bird logo.

Today, however, that same webpage — ads.twitter.com — appears without either mark. While a Google search still displays the hyperlink title “Advertise on X (Twitter)” and X Corp.’s new suit indicating that users still access the platform through the domain “twitter.com,” such residual references may not qualify as bona fide trademark use. X Corp. also proffered within its new suit that they still actively defend and maintain the Twitter trademarks, but those efforts still may fall short.

Given the marks’ apparent absence from active branding, the USPTO and Delaware District Court will need to determine whether X Corp. can demonstrate a concrete and ongoing intent to resume use of the Twitter marks. Perhaps revival plans exist behind the scenes or perhaps the blue bird has truly flown the coop.

If X Corp. fails to muster up the evidence and the marks are deemed abandoned, maybe a new social media tycoon may well be born from Twitter’s discarded feathers. Until then, we can perch by our windowsills and watch how it all unfolds.